Early Impressions

by Hermia Thomson

p. 55

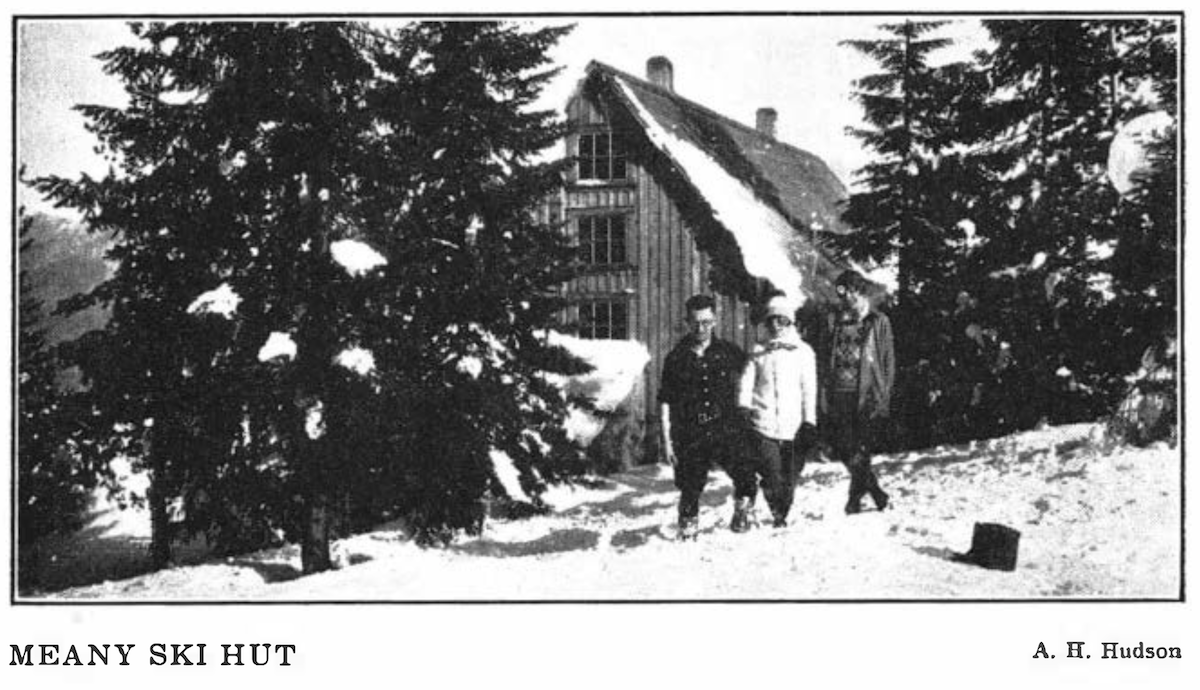

PHOTO - MEANY SKI HUT by A.H. Hudson

It is Indian Summer, and a certain crispness in the atmosphere-a tang in the morning air or a tinge of frost in the moon-touches some responsive chord within that crystallizes vague anticipation of approaching glorious days in the snow. How easy, upon closing my eyes, to imagine myself with ski-poles in my hands and a pair of willing servants beneath my feet, on the white mantled slope of a moon-swept hill, trees in a dark line behind, before, the far-flung mystery of winter mountains.

The scene changes, I think of a glowing fireplace in a big friendly log room, snow piled against the windows, a line of mittens and caps steaming under the mantel, skis warming before the stove, the hearty companionship of many friends making an atmosphere unique in its genuine friendliness and common enthusiasm.

In this reflective mood I take down ski-poles to make sure that their shafts are intact and rawhide sound, and I pass a reminiscent hand down the smooth surface of each faithful ski. I catch a faint odor clinging to sundry accessories strongly suggestive of Hopskivoks and Klister. The glimpse of a small label “made in Norway” sets my blood tingling with treasured memories of the past winter’s joys and shadowy visions of what lies waiting after the passing of a few autumn weeks.

To one who has never become acquainted with the exhilarating pleasures that skiing affords, there is a decided mixture of feelings the first time he buckles a pair of the slippery boards on his feet, gives his cap a final tug, and grasps a ski-pole in either hand.

p. 56

Drawing a long breath, he heads for the pitfalls which, though invisible as yet, he knows exist in the long, white slope before him. Perhaps foremost in his immediate emotions is the antipathy he feels for a fall. He cannot do himself a physical injury on a gentle slope in six feet of soft, yielding snow, but there is something that causes a disrelish for a complete upset of equilibrium. Every time one falls, he must collect poles and wits, and compose his apparel and his spirit before regaining the balance of body and mind indispensable to a vertical skiing posture. Before he has made many descents the novice learns that he is helpless, hopelessly inadequate, and entirely unequal to the situation at hand when he has fallen with his head abruptly downhill in spread-eagle attitude, his hands unable to find any solid foundation, and his feet despairingly treading powdery snow.

However, this aversion to tumbles is a transient emotion. When experience has taught that a body which is momentarily out of control, if relaxed and loose-jointed, can bring nothing further than a temporary respite from smooth glissades, and a great clacking of skis and poles, with its consequent audience of invariably interested onlookers, he ceases to have apprehensions of falling and becomes occupied with the business of surmounting the obstacles in his path.

There is variation in the ability of neophyte skiers. Some, to judge from the speed with which they adapt themselves to the intricacies of the art, would seem to have a little Scandinavian blood in their veins, and to these the dream of exhilarating descents and delicate maneuvers soon become a working reality; but others to whom adaption to a new sport is not so rapid, merely need a longer period of endeavor; And perhaps these last are to be envied, too, for theirs is the eager and whole-hearted fun of learning.

Once a person has gained the first slight mastery of the thrilling art, what is it that causes him to fall so deeply in love with skiing that he is its slave thenceforth? Is it that its perfection is some elusive will o’ the wisp that calls and beckons one, leading him on, over rough places and hardships of which he is but dimly aware? Or is it that after one has a taste of the exhilarating sport with its accompaniments of glorious companionship and the mountains’ mid-winter beauty he can find no substitute but what seems dull and prosaic? Whether it be one of these reasons or an intangible something that evades expression, it remains that the skier will follow the snow higher and farther into the hills as it recedes in the spring, and in the fall will welcome the first opportunity to dig out the square-toed boots and to put a coat of wax on beloved skis.

Skiing is appealing alike to man and woman, to the adept and the inexperienced. And not only to the expert are the tangible rewards due.

p. 57

Trophies are awarded to winners in skill and endurance, and occasionally it is the person who in the early winter made his first long remembered glissade who will in the spring glide down the trail with a silver cup stowed away in his pack. It has been done, and it will be done again. It needs no urging for the lover of snow to buckle on a pair of skis and to fare forth to the upper slopes where every angle is rounded and every rough contour softened by a covering of virginal beauty.

Skaal to the ski! May it stand as a symbol of man’s love of Nature’s handiwork and a whole-hearted enthusiasm for an inspiring and exalting activity.

Skaal!